How To Choose Your Best Hunting Scope

Tough. Durable. Consistent. That’s what you want in a hunting scope.

Despite our best technology -- HD glass, illuminated reticles, ballistic reticles, dial turrets, parallax adjustment dials and 8X zoom ranges -- a riflescope is really just a front sight. Yes, it is magnified and glorified, but still, its main job remains pretty basic —keep pointing where the barrel delivers bullets. The brightest, most powerful scope in the world is useless if it can’t hold zero. So put durability first on your list of qualifications for a hunting scope.

Identifying Durability in a Hunting Scope

Of course, durability is a relative term when you’re dealing with a complicated, mechanical instrument filled with glass. No matter how tough they are built, scopes remain the weakest link on most rifles. If anything is going to break or malfunction during any hunt, chances are it’ll be the scope. For this reason I always carry a backup scope on hunts far from home, one already mounted in Leupold or Talley quick-detach rings and zeroed to my rifle and load. This backup scope doesn’t have to be a fancy model, but a rugged one. The engineers at Leupold tell me their least expensive scopes are as rugged and durable as their most expensive — and hold zero just as reliably. That’s the kind of assurance I like in a backup scope. Over the years I’ve inadvertently tested this to my satisfaction, having dinged, banged and dropped Leupold scopes from Arctic mountains to African deserts. None has ever failed. I’ve bashed a few hard enough to knock them off sight, even to put dents in them, but after re-zeroing, they went right back to work.

I'm sure other brands are this rugged. I just haven’t had as much experience with them. If you have, stick with the scope or brand you believe in. Durability is tough to shop for. How do you recognize it? Manufacturer guarantees and warranties are a good hint. Lifetime guarantees — the kind that say a company will repair or replace a scope for any reason — suggest the maker doesn’t think too many of its scopes are going to break. This doesn’t prove they are the most durable, but strongly hints at it.

To check mechanical scope quality in the store, turn all the moving parts. Any grinding? Any rough spots?

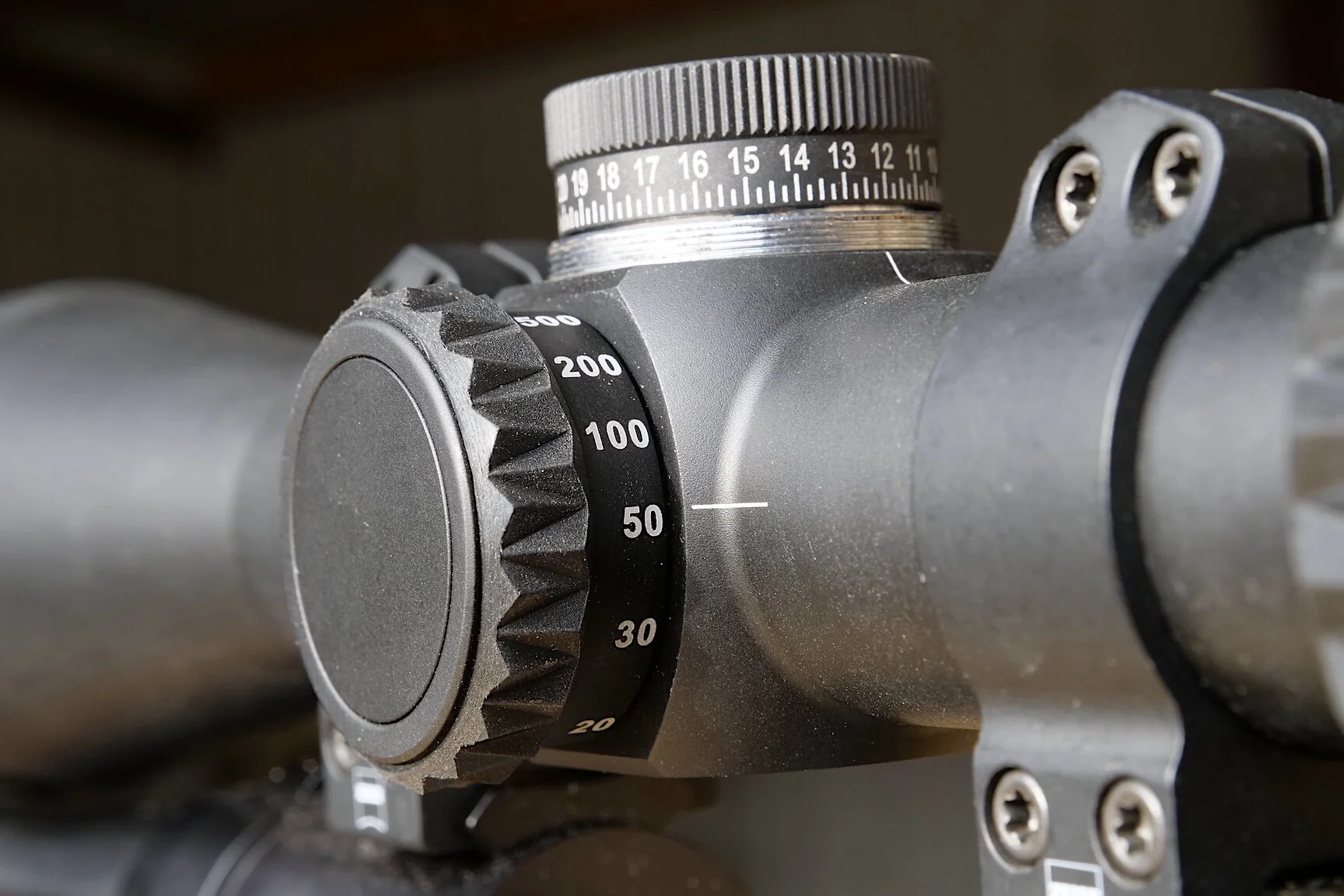

To test a new scope for basic function, twist and turn all the moving parts, feeling for any rough spots or glitches. Dial turrets against a one-inch grid target and verify movements. Lock the scope on target and zoom the power ring, watching to see if the reticle moves off point-of-aim. Truly testing durability requires use and wear, but you can get an initial confirmation of a solid build by firing at least 20 rounds with your new scope mounted on your rifle. Forty would be better. That's usually enough to shake loose anything that wasn't tied down properly. If the instrument runs fine for 40 rounds, it's probably good for 4,000.

How Much Magnification?

Don’t fall for too much scope power. A 1-4X or 1.5-6X is fine for dangerous game, woods hunting and anything out to 200 yards. Most all-round hunting to 400 yards or so can be handled with a 3-9X or 4-12X, but you might like something up to 18X or 20X. More magnification than that can become a hindrance at close range and a rare-use specialty for long range. Just remember that 10X power makes targets appear to be ten times closer, so a deer at 500 yards would look like one at 50 yards to your naked eye. Most of us can hit a deer with open sights at 50 yards!

What You May Not Need in Your Hunting Scope

What you probably don’t need in a general purpose hunting scope are an oversized main tube or a huge objective lens. A larger main tube does not increase brightness, but does provide more room for turret adjustments. If you’re not dialing for extreme-range shots, a 1-inch main tube will keep your rig smaller and lighter. Those 50mm to 56mm objectives do admit more light into the scope, but you might not need it. High-quality, fully multi-coated scopes transmit 90% or more of the light that enters them these days, and at 8X even a 40mm objective produces a 5mm Exit Pupil. That’s more than enough light to clearly see a black reticle against the hide of a mule deer, elk, and even a black bear a good half-hour after sunset, if not a full hour later. Shooting hours in many states end a half-hour after sunset anyway. Objective lens diameter divided by magnification produces the exit pupil in the eyepiece. If this equals or exceeds the dilation of your own pupil, you’re taking in all the light you can. The human pupil opens to more than 5mm well after sunset, so you can’t take advantage of an exit pupil that large or larger for more than perhaps an hour a day. After age 50 or so many pupils lose their ability to open more than 5mm, so a 6mm to 7mm exit pupil is wasted. Why put up with the oversized objective? You can always increase exit pupil size (thus image brightness) by dialing power down. A 50mm objective at 10X = 5mm EP. A 50mm objective at 8X = 6.25mm EP. Dial down to 6X and exit pupil widens to 8.3mm!

Ballistic Reticles or Turrets?

Choose turret dialing or ballistic reticles if you like, but neither is necessary for shots inside 300 yards or so with most modern, bottlenecked cartridges. Unless you are extremely fast and competent operating an elaborate scope, you might be better off with a simple duplex reticle and a Point-Blank-Range sighting system (read all about that in this RSO post.) This will suffice for well over 90 percent of your shots.

The more moving parts on a hunting scope, the greater the chance to screw up!

If you do want/need to shoot long range using a laser rangefinder and BDC reticle or turret dialing, make darn sure you train with it. A lot. Most hunters get so excited, even flustered, when a big buck or bull appears that they’re lucky to remember how to flick off the safety let alone calculate drop, estimate wind drift, compensate for that, turn the dials or select the right sub-reticle. The more complicated your scope, the more opportunities you’ll have to screw up. If you get one this advanced, train until you can run it half asleep. Arriving in a remote hunting camp with new, complicated scopes and magnum rifles is probably the most common mistake hunters make. The animals love it, but all those misses will drive you to tears. If you’re convinced you’ll be forced to take many 300- to 600-yard shots, you’ll want a scope system that can handle that. Just know that most game is shot inside of 300 yards. Don’t get so preoccupied with complicated sighting systems that you end up fiddling indecisively when you should be concentrating on your shot.

Lens Coatings Help Make the Perfect Hunting Scope

With any optical tool, get the best anti-reflection coatings you can afford. The more the better because these coatings maximize light transmission and minimize glare and flare without extra bulk or weight. When your shot is looking toward the setting sun, you’ll appreciate anti-reflection coatings that minimize flare and glare. These coatings provide the biggest bang for your buck in optical performance.

Tough exterior lens coatings minimize scratches, shed dust and rain, and extend the life of the scope.

Exterior lens surface coatings designed to shed fog and fingerprints or resist scratching, like Leupold’s Diamondcoat, Swarovski’s Swaroclean, and Zeiss’ LotuTec aren’t absolutely necessary, but good protection against dust and fogging.

HD Lenses

HD and ED lenses are more hyped than understood. They are a certain type of fluoride glass that minimizes something called color fringing. Basically this makes objects look sharper, crisper, better defined. Fluoride lenses don’t contribute much at less than 10X magnification, but at 15X and higher they really begin to make a difference. However, since a riflescope is an aiming device, not a game location and identification instrument, I don’t feel HD/ED lenses are of major benefit. If cost is no object, I’d sure get them. Otherwise I’d save my money for HD glass in my binocular and spotting scope.

Illuminated Reticles

This is a personal choice. I’ve never found them necessary for putting my aiming point on target, but my wife does. A little red center dot helps her focus on the precise aiming spot. She’s not alone. Many shooters find that illuminated reticles enhance concentration and build confidence. When that tiny red dot hovers over the sticking place, you know you’re on.

Eye Relief

Often overlooked, eye relief (ER) can make the difference between a pleasant shot and a sharp cut above the eyebrow. ER is the distance from the ocular (eyepiece) lens to your eye when you have a full, complete view without edge blackout. ER is set for each scope at the factory and cannot be changed by the user except slightly by turning the diopter adjustment ring. This moves the ocular lens in and out to accommodate different users’ eye strengths. Most scopes come with anywhere from 3 to 4.5 inches of ER. On a hard kicking rifle, or for shooters who creep forward on the stock (commonly done when excited or shooting steeply uphill,) a minimum of 3.5-inches ER is smart and 4 inches is smarter. On any scope, note how far the ocular bell or housing protrudes past the actual glass lens, too. Then consider how far your brow protrudes beyond your eyeball. Added together, these two protrusions could knock off a half-inch offfunctional ER. After all, it is your brow and that metal eye ring that are going to connect.

Eye relief is the distance from your eyeball to the scope’s eyepiece lens, but functional eye relief is the distance from your brow to the scope’s eyepiece rim. Those are the parts that meet during hard recoil. Eye relief is built in and can’t be changed. Get 3.5 inches or more.

Cleaning Kit

A lens brush and microfiber cloth in a plastic baggie will suffice if you use them. Dust piles up quickly on lenses to dim the view and increase flare. A quick brushing at mid-day and each evening should optimize your sighting picture. Avoid wiping unless oil and gunk befoul the lenses. Liquify the gunk and wipe gently many times instead of pressing and grinding hard one or two times. You're trying to lift debris off the lens, not grind dust and sand into the lens. You can buy a complete, compact field optics cleaning set here.

Conclusion

Remembering the function and purpose of a hunting scope should help you resist the urge to buy more than you need. Elaborate and complex parts and functions are useful, even essential, in a target scope, but can get in the way on a field scope. Assess your needs soberly. Then shop for mechanical precision and durability followed by optical quality. Consider the manufacturer’s reputation and warranty. You can find acceptable performance and amazing durability in simple, surprisingly inexpensive scopes used on light-recoiling rifles. But the more elaborate the scope, the more its moving parts, and the harder kicking your rifle, the more quality you should demand.