How To Choose the Right Rifling Twist

Way back in the late 1400s an inventive gun maker added a new twist to firearms — rifling. And shooters have been confused about rifling twist rates ever since.

Primitive blackpowder firearms spit balls from smooth bores and the words “accuracy” and “gun” weren’t used in the same sentence. Musket balls were cast smaller than bore diameter so they’d be easy to ram home, especially after one or two shots had layered soot down the barrel. Balls probably rattled on their way out.

Primitive Rifling Twist First Tried

By the late 1400s, gun makers concocted the first crude rifling in an attempt to mimic the spin effect that fletching gave to arrows. True rifling, as we know it today, didn’t appear until the mid-1500s, and then it was probably used only in specialty guns because they were so slow to load. The British army was still shooting smooth bore muskets in 1776, a big part of the reason General Washington and his backwoods hunters shot them to pieces with their rifled flintlocks.

How Rifling Twist Works

After our Revolutionary War, rifling became the best game in town. If you wanted to shoot straight, you shot a rifled barrel. The word rifle comes from an old German word meaning to groove or furrow. To rifle a barrel means to put curving grooves into its bore.They can be cut in (cut rifling,) pressed in (button rifling) or hammered in (hammer forging). Bullets fired down rifled bores must be slightly larger than bore diameter so they can be gripped or engraved by the rifling. This is why 30-caliber cartridges are loaded with .308" bullets instead of .300" bullets, 28-calibers shoot .284" bullets and .22s spit .224" bullets.

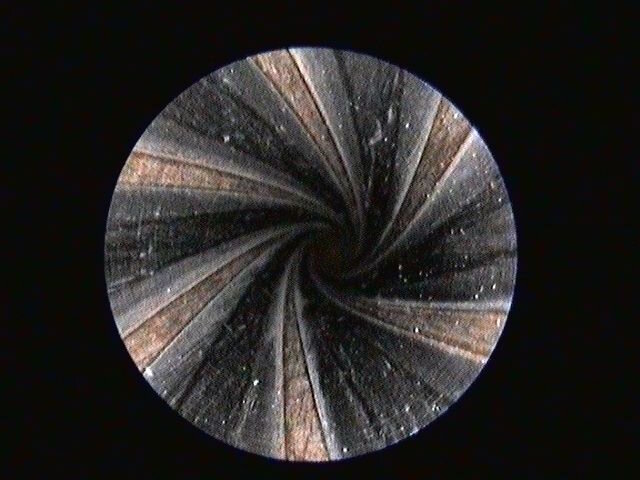

Cutaway barrel shows the rifling as angled line in front of the bullet. The rate at which that groove turns determines spin of the bullets passing down it.

Because rifling grooves grip bullets so securely, the projectiles must follow the turning path of the rifling, and that's what gives them their spin. The bullet's velocity and the degree or rate of the rifling's turning determines it revolutions per minute, which can be as high as 330,000 rpms. You can see a bit of a barrels rifling by looking at the end of the muzzle, but for a really good look you need the magnified view provided by a Hawkeye borescope. One of those was used to take the picture at the head of this article.

Today rifled barrels are routinely used on handguns, cannons, rifles of all kinds and any barrel designed to spit a single projectile accurately. Even shotguns can wear rifled barrels, which technically makes them rifles. Anyone who has shot slugs from a true smoothbore shotgun barrel and then switched to a rifled barrel understands the accuracy advantage, but might not fully understand why.

Why Rifling Twist Is Critical

Why are rifled guns more accurate than smoothbores? Gyroscopic stability. If an elongated projectile (bullet) didn’t spin, it would tumble. Even though musket balls can’t tumble, since they’re the same shape on all “sides,” they still fly straighter if spun. Like a spinning top, a spinning bullet resists forces (in this case variable air pressure) from any side, so it better maintains its original flight vector.

The rate of spin is important. The longer the bullet, the faster it must be spun to remain stable in flight. This necessary spin rate is determined by the rifling’s rate of twist, which is the linear distance needed for the grooves to make one revolution. A slow twist rate would make a complete turn in 48 inches of forward travel. A faster twist would turn a full circle in 14 inches of linear travel and a super fast twist would be one turn in 9, 8 or 7 inches.

Long, sleek bullets like this Cutting Edge, Barnes TTSX and Berger VLD, all in .284, need fast twist rates to stabilize in flight.

Barrel Length Doesn't Change Rifling Twist Rate

A 48-inch, slow twist barrel doesn’t have to be 48 inches long to work properly. It’s the rate, angle or degree of the rifling twist, not the linear distance, that matters. A groove that turns at a degree sufficient to complete a full turn in 48 inches is a 1:48” twist rate regardless of barrel length. If the rifling grooves make a complete revolution in 9 linear inches, it is a 1:9” twist whether the actual barrel is 9 inches long, 30 inches long or just 3 inches long.A bullet traveling down a 12-inch barrel with a 1:14” rate of twist will still be spun at the 1:14” rate. A 3-inch barrel with 1:14” twist spins its bullets the same as if it were 14, 24 or 48 inches long.

Shooters talk about twist rate a number of ways, but if asked “What’s your barrel twist?” most answer “It’s a one-in-ten twist,” or just “Ten.”

What Rifling Twist Do You Need?

What puzzles many shooters is exactly which twist they need for a specific cartridge. That’s the wrong question. It’s not the cartridge that determines necessary twist, but the bullet. The longer the bullet, the faster it must be spin to remain stable. Manufacturer’s take care of this by building to accepted standards. SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute) publishes standard twist rates for various cartridges. These aren’t, however, mandatory, which is why you can buy 223 Remington chambered rifles with 1:14, 1:12, 1:10, 1:9 or 1:7 twist barrels. Oddly, the 22-250 Remington, which shoots the same .224” diameter bullets as the .223 Rem., is usually offered only with 1:14 or 1:12 twists. Virtually every 30-06 is made with 1:10 twist, but various 6.5mm cartridges might have rifling twists from 1:11 to as fast as 1:7.

L. to R: 223 Rem., 22-250 Rem., 22-250 Ackley, 220 Swift. Each case can fling the 75-gr. Scirocco and 70-gr. Barnes TSX shown, but the twist of their barrels might not be fast enough to stabilize them.

Why so much variability? It starts with original cartridge/bullet design. The 30-06 Springfield, for instance, was initially engineered in 1903 as a military cartridge firing a stodgy, 220-grain round nose bullet, changed in ’06 to a 172-grain spire point, later a 150-grain. A 1:10 twist adequately stabilized the 220-grain round nose, which made it more than fast enough to stabilize the lighter, shorter bullets, so the 30-06 twist rate standard remained 1:10. Today’s long, 220-grain, sharply pointed, boat-tail VLD bullets might not be stabilized by a 1:10 twist barrel.

Many of our 6.5mms started life as military rounds in other countries where they were loaded with extremely long bullets. These required fast twist rates. Our 5.56x45mm NATO/223 Remington was originally designed around a 55-grain bullet and 1:14 twist. To improve downrange performance they went to a 62-grain bullet and 1:9 twist. The U.S. military uses some 77-grain bullets, too, and they generally require a 1:7 twist. In any caliber, the longer the bullet, the faster the rifling twist needed to stabilize it.

Production 22-250 Rem. rifles are rarely offered with fast twist rifling because the 22-250 Rem. was designed around 55-grain varmint bullets almost 100 years ago (but not released as a factory, commercial round until 1967). Back then no one imagined shooting long, skinny, aerodynamically efficient 75-grain bullets in the 22-250, so why use a fast twist? Today, handloaders build custom 22-250 ammo with bullets as heavy and long as 90-grains. Those need 1:7 twists to stabilize. Gunsmiths appreciate the rebarreling business.

Your Preferred Bullets Will Determine the Rifling Twist You Should Buy

A collection of .224 bullets. The longer they get, the faster the twist rate needed to stabilize them.

When buying a rifle, you can just accept whatever twist is offered and buy ammo/bullets to match. If, however, you want to shoot long, high B.C. bullets, you’ll need to specify a fast twist barrel. The best way to determine the twist you’ll need is by consulting the bullet maker. Hornady, Barnes, Berger, Nosler, Cutting Edge, etc. recommend twist rates for their extra-long, non-traditional bullets. Hornady, for example, recommends a 1:8 or faster twist barrel for its .243 108-gr. ELD Match bullet. Berger recommends the same 1:8 for its 82-gr. .224 Match BT Target bullet and many others.

Now, if you’re worried about something called “over stabilization,” stayed tuned. We’ll address that in another article here on RonSpomerOutdoors.com.

Conclusion

The current fad toward long range shooting has led to ever longer, more ballistically efficient bullets. Fast twist barrels are necessary to stabilize those in any caliber.

Some say Ron Spomer's interest in guns, bullets and ballistics has left him a bit twisted. He prefers "stabilized."