Happy Birthday to Us

I don't make a big fuss over birthdays, but they are a reminder to reflect, especially when more have faded in the rearview mirror than will approach the windshield. My resume' is padded with plenty of mistakes and sorrows, but more accomplishments and joys. I should certainly count my blessings. But I must also thanks those who made them possible. Thanks to the efforts of the generation that came before mine, the natural world I've loved and enjoyed was not just saved, but restored. Because hunters in the 20th Century grew alarmed at declines in waterfowl, deer, elk, sheep and even songbirds, they sounded the alarm, pushed the legislation and created the incredibly successful North American Model of Wildlife Management. Based on the common-sense reality that wildlife is a renewable resource that belongs to everyone and has value, hunters devised a system in which wildlife earned its keep. It bred and thrived and filled our world with life. We paid to hunt the annual surplus. The money thus raised funded biologists and conservation officers who guarded, transplanted, researched, protected, enhanced and otherwise improved populations of wildlife. When I was a kid, our rural landscape held no whitetail deer. Canada geese were denizens of the northern wilderness. Pronghorns and elk were remnants of the past clinging to existence far out West. Bighorn sheep had been wiped out in dozens of former haunts. Turkeys were golden brown and came out of ovens. On and on it went. But improvements were already underway. Thanks to millions upon millions of dollars handed over for licenses and tags -- plus millions more voluntarily paid in excise taxes on guns and ammo -- we were correcting the abuses of the past. Wildlife was surging back. We bought and restored wild habitats, saved wetlands and streams, stopped overgrazing and overcutting and cleaned up our waterways. We still built too many highways, plowed to many grasslands and damned too many rivers, but -- despite the ongoing destruction of land to accommodate humans in the lifestyle to which we desired to become accustomed -- our wildlife management efforts succeeded in helping numerous hunted species roar back, even while un-hunted species like golden-winged warblers and ivory-billed woodpeckers slipped toward extinction.

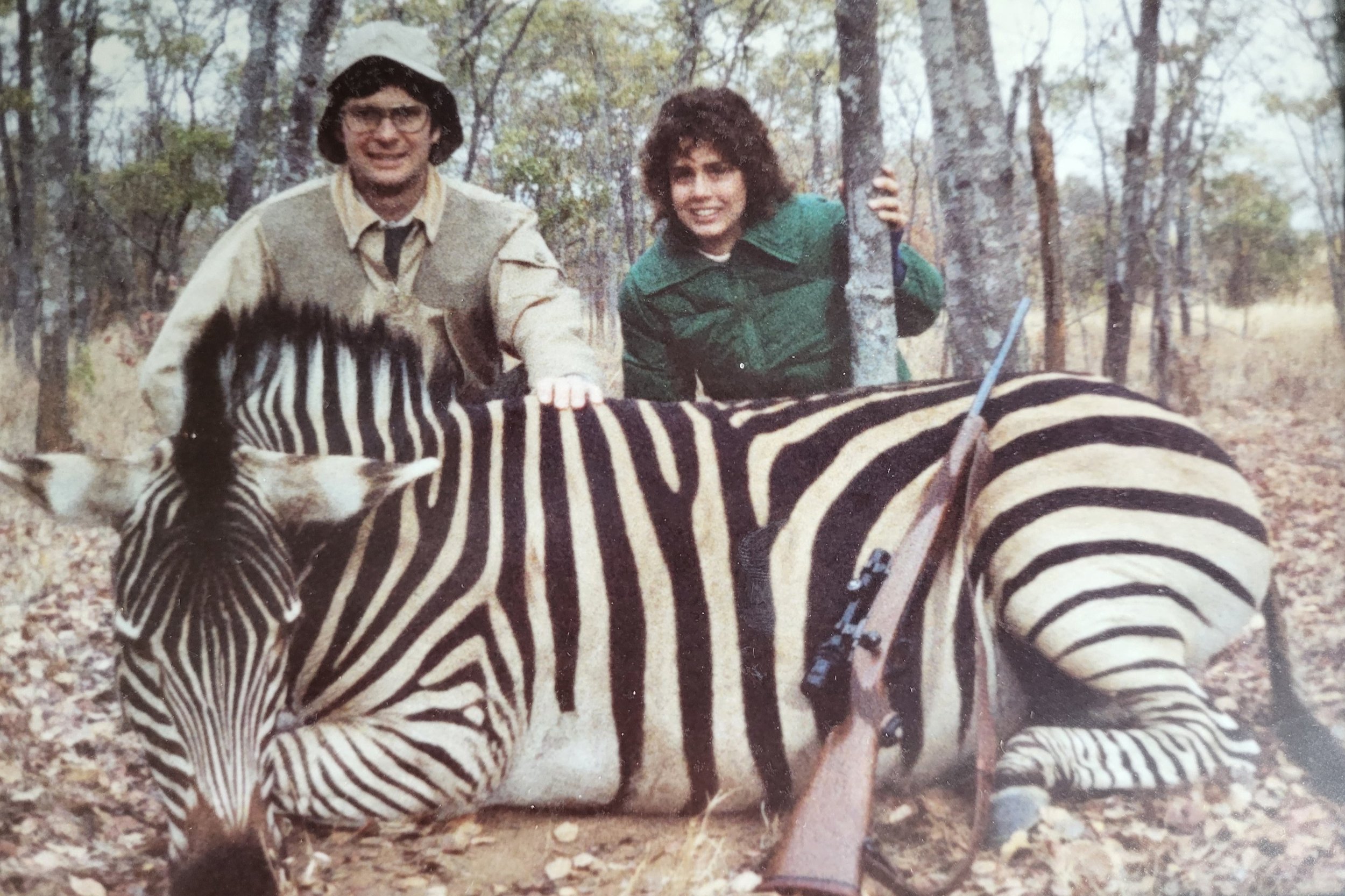

Society at large didn't amass a great track record on the environment, but we hunters did more than our share. Thanks to that work I've gotten to hunt in wild places unchanged from when Lewis & Clark first saw them. I've eaten pure, all-natural, organic, free-range meat fit for a king. I've seen whitetails leaping across fields where they'd never been before; heard turkeys gobble in woods that were mere dirt in 1970. I've photographed polychromatic wood ducks dabbling on lovely waters that were ugly erosion scars in 1964, and I've caught trout from streams that were chemical dumps in 1955. Yes, I was incredibly lucky. Like most Baby Boomers, I enjoyed the best of times, perhaps the perfect combination of safety, comfort, access, abundance and wild Nature. And I'm incredibly grateful. But will our grandkids be? What we restored and saved in the 20th Century is in serious jeopardy in the 21st. We need new conservation heroes, everyday men and women who'll sound the alarm and man the pumps. An ever increasing human population coupled with our cultural withdrawal into a suburban, digital world spells trouble. We fought a good fight for wildlife, but it isn't over. Birthdays or no birthdays, our wildlife legacy is squarely in front of us. We can study the rearview mirror for inspiration, but it's the windshield view that matters.