Mom Is Waiting for Her Hunters

_MG_3294 copy

We will lay Mom to rest today in the black prairie soil just six miles from the sod farm house in which she was born 89 years and nine months ago.

Despite having grown up on a farm surrounded by ringneck pheasants, Mom didn’t like wild game. She didn’t like guns, either.

It’s not that Mom didn’t appreciate what firearms could do. She just thought they were dangerous. Too dangerous for her boys. I’m pretty sure she coined the phrase “You’ll shoot your eye out!” I wasn’t allowed to have a Daisy BB gun until I was 13 and earned one by selling newspaper subscriptions. My brother and I have since owned several dozen rifles, shotguns, muzzleloaders and handguns. I still have two good eyes. So does my brother. But we no longer have Mother.

For 60 of her years Mom was a hair dresser. She managed her own shop, usually putting in ten-hour days, six days a week. Yet she somehow found time to help with annual harvests, teach Sunday school and sing in the church choir. She baked hundreds of pies sold in Dad’s restaurant, waited tables, washed dishes and cooked ethnic German foods once a week. She grew a vegetable garden, canned each winter’s supply of fruits and vegetables and even made homemade lye soap. A perfectionist, she somehow found the energy to crochet, sew, quilt, paint ceramics and sit up waiting, always waiting, until her boys straggled in, wet and hungry from yet another duck or deer hunt.

_MG_7558

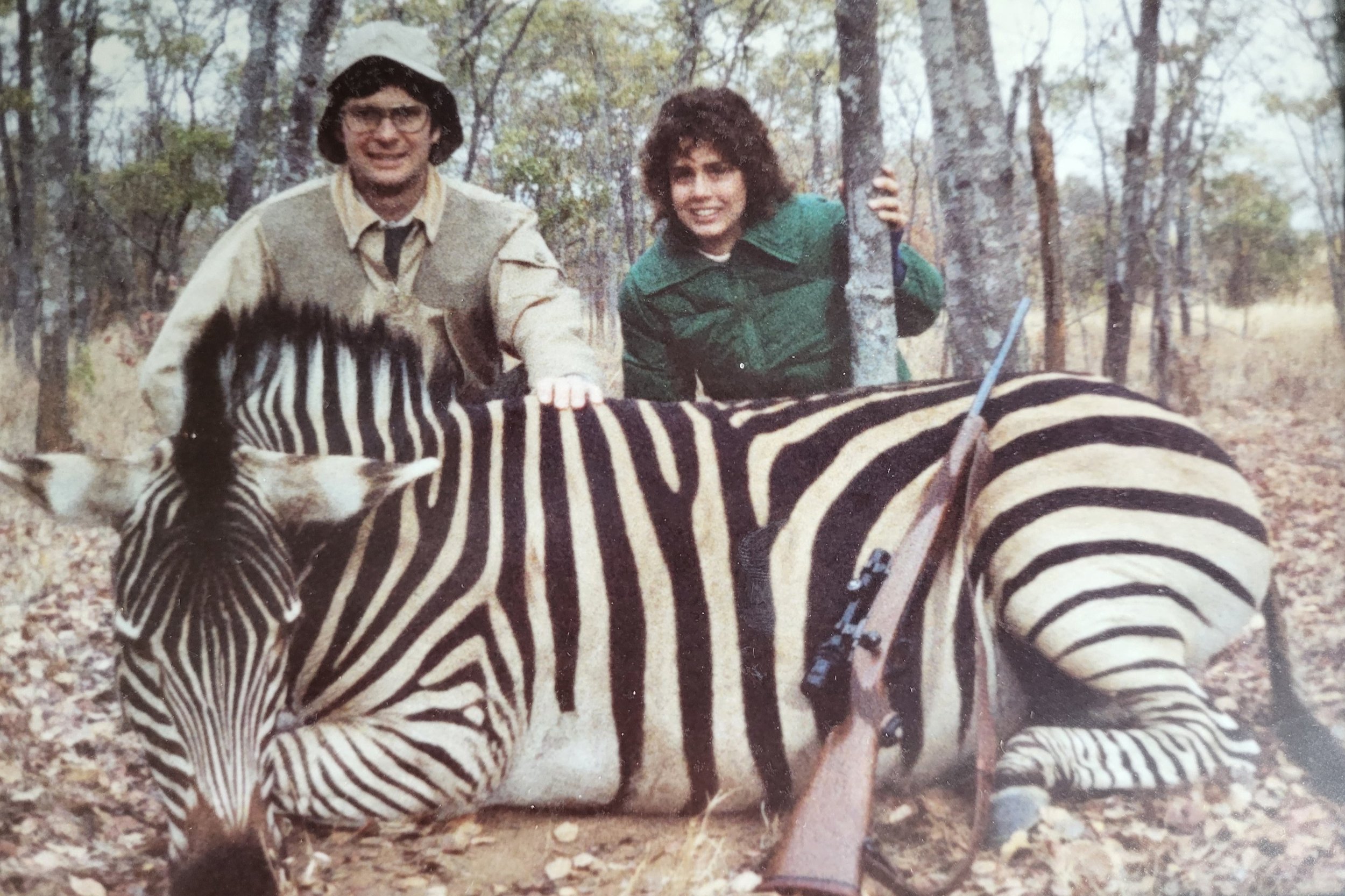

Mom was not a hunter. The wildest thing she ever pursued was a fly, yet she prepared elaboratedinners with the game her boys brought home. Mom could spend more time picking pin feathers from the skin of a pheasant than it had spent growing them.

Mom grew up with Grandpa’s shotgun by the front door. She’d undoubtedly seen him use it to shoot foxes and badgers prowling round the hen house. Having lost his savings in the crash of ’29, Grandpa was forced to pull his family through the Dirty Thirties largely by subsistence farming, and there wasn’t much rain to help with that. Chickens weren’t a novelty; they were essential, and Mom was tasked with feeding them, locking them in at night and gathering their eggs each morning. Then she and her sister would herd the milk cows to graze the roadside borrow ditches.

Those hard years taught Mom industry, frugality, perseverance, fidelity and an appreciation for the finer things in life. Guns and hunting weren’t part of that; protecting and nurturing her family were, and she pursued those ends relentlessly.

In this context Mom’s acceptance of our hunting and shooting passions was all the more remarkable. Somehow, despite her fears for our safety, she understood our great need to pursue our outdoors passions with her support. Each time we left the house we heard her warning: “Now be careful with those guns!” And then she would work and paint and wait up through the cold and storms, worrying sleeplessly until we returned, safe and secure in the restorative warmth of the home she and Dad had made us even as they gave us the strength and courage to leave it.

This caring did not end. Not when we had homes and families of our own, not after Dad died and she was alone, not when she lay dying and knew we were racing to her side. She hung on, unable to speak, to open her eyes, to murmur or blink. Yet she clung to life as we drove 1,300 miles to reach her, to say our good-byes, to thank her for all she had done for us and to give her permission leave us. “It’s okay Mom,” my brother said. “If you see Jesus beckoning, you go with him. We’re okay.”

She struggled another hour as I held her hand and told her she could go to see her beloved husband, to say hi to Dad for us and tell him we missed him. At this I felt her hand tighten ever so slightly. I left her at midnight in the care of the most wonderful nurse, my wife, who later spoke of a change that came over Mother after we boys had left. Her breathing slowed, she calmed and quietly floated away to where she waits for us to come home from our final hunts.

Mom 5-17-09

# # #