The Truth About Bullet B.C.

High B.C. bullets are not just popular, they’re like awesome, man. Cool. Sick. Really rad. Ballistic Coefficient rules!

But will high B.C. bullets put tenderloins on the grill? Will they spell the difference between DRT and tracking city? Hit or miss?

Once again it’s time for the tale of the tape.

Will sleek, sharp, boat tail bullets really make a difference in big game hunting? Or are they mostly hype?

Every Bullet B.C. Number Tells a Story

We will compare two bullets departing the station at 2,850 fps. Why that speed? Because it’s about what many of our popular deer cartridges do, give or take 100 fps. Besides, the start speed doesn’t really matter since both our projectiles will match it. What they won’t match is Ballistic Coefficient. That will be the difference. One will be a 150-grain Round Nose, B.C. .186, the other a 150-grain boat tail spire point, B.C. .415. Caliber and SD (Sectional Density) do not matter either because both are already factored into the B.C. number, as is weight, but just to make this ballistic race a bit more real for us, know that these are .308 bullets. The Sectional Density (SD) of both is .266. Both are zeroed for their MPBR in a 10 mph crosswind.

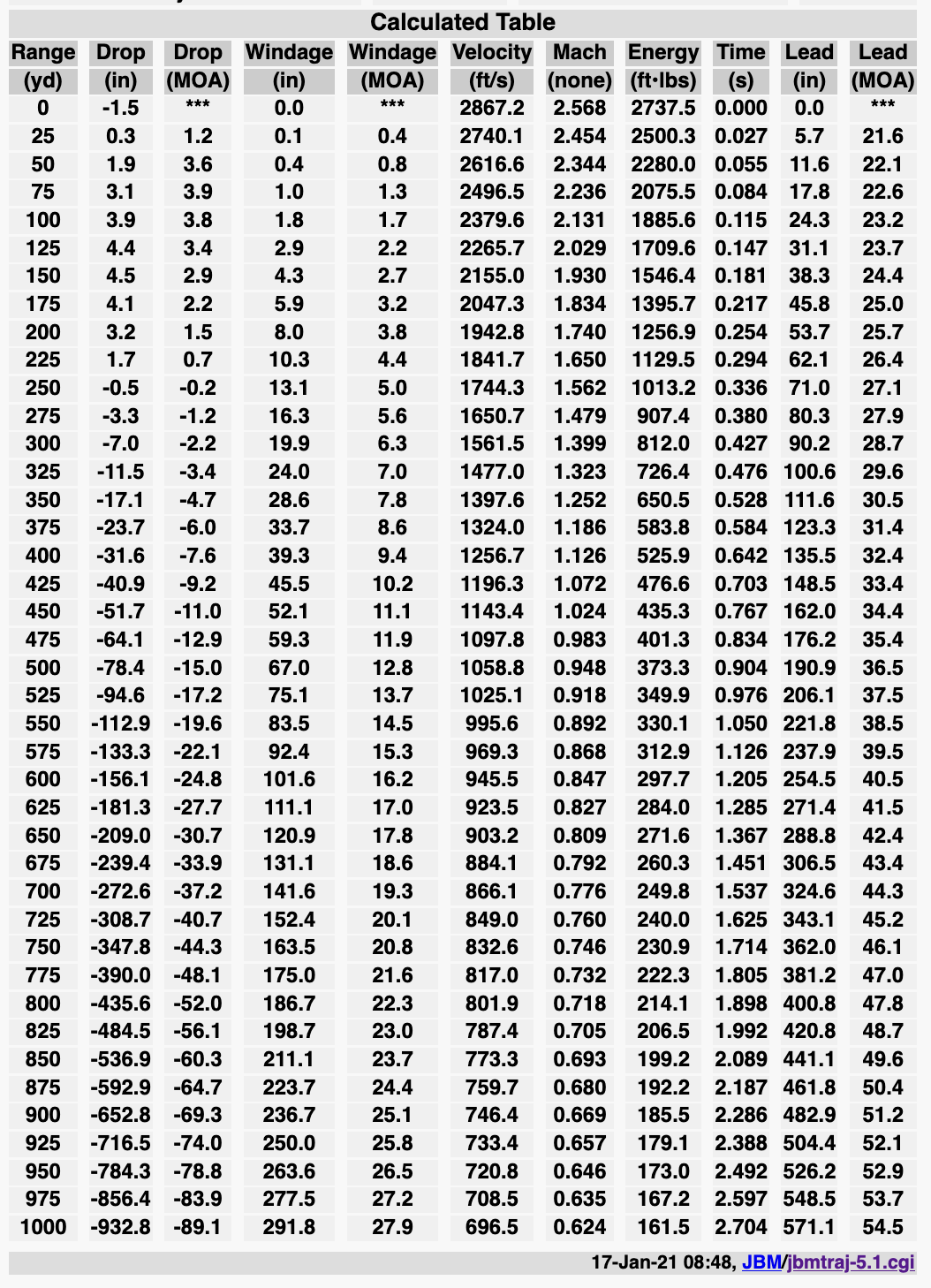

.308, 150-grain Round Nose, B.C. .186

.308, 150-grain BTSP, B.C. .415

Drifting Away

Study those drops (2nd col.) and drifts (4th col.) for a minute and you might be surprised to see that at 500 yards the higher B.C. bullet drops 42 inches less than the low B.C. bullet. That’s just over three feet! It also deflects 44 inches less in that 10 mph crosswind. That much difference from the same caliber and weight bullet with the same SD! And all because of atmospheric drag.

If excessive drop and drift don’t concern you, consider the lost energy (8th col.) That stubby, inefficient round nose bullet gives up 752 foot-pounds of energy to the boat tail spire point. Neither energy level is what I’d prefer to apply to an elk, which is why it’s silly to be trying to target game at 500 yards with low B.C. bullets. (Yes, in the rarefied world of high B.C. bullets, .415 is pretty low.) Many hunters are convinced it’s foolish to target an elk at 500 yards with any bullet.

Targeting a bull elk at 500 yards is not the best idea. I squeaked in just under the limit at 450 yards with this Wyoming elk. A 150-grain Barnes TSX from a 5-pound Rifles, Inc. Strata Stainless in 280 AI did the heavy lifting. That uber-light rifle shoots around 1/2 MOA and has accounted for a lot of game from Coue’s deer to moose. I usually keep a Leupold VX-3 2.5-8X36mm scope attached to it with Talley One-Piece rings. A light rig like this makes mountain hunting less arduous. That Zeiss 8x32mm Victory binocular is another bright, light mountain option. When mountain hunting, light makes right — and the older I get, the righter its gets!

Friends, say what you will about B.C. being a pile of “bull shoot,” but you’ve got to concede these are huge differences. And all because of B.C. That means form factor. Not weight. Not SD. Not starting velocity. Those are all constant. It’s just each bullet’s shape that made the trajectory differences.

Differentials like these are why long range shooters are so fixated on high B.C. bullets. But do hunters have to be?

Getting Pragmatic About Bullet B.C.

That depends on how you hunt and how far you can or will shoot. Check those numbers again and note that at 300 yards the drop advantage for the boat tail is just 5 inches. A careful hunter and precise shooter could probably succeed with that. But look at that wind deflection difference. It is 13 inches! That’s a significant problem for accurate shot placement. Aim for the heart and hit a foot downstream and you’ve got yourself a paunch shot.

Then there’s that 300-yard energy difference: 822 foot-pounds! Why would anyone give up 822 f-p of energy just to shoot a round nose bullet that generates the same recoil as the boat tail spire point?

But that’s at 300 yards. What if you’re one of the millions who rarely or never shoots at game beyond 100 yards? Well go to bed early and sleep the sleep of the innocent. At goal post distance there is so little difference between these two bullets that you can ignore it. Unless you’re trying to head-shoot mice.

A whitetail’s vital zone is large enough that a couple of inches more drop and drift probably isn’t going to matter.

Does this then mean that you should ignore B.C. and shoot whatever you like until beyond 200 yards or so? Well, you could, but why? Shooting a higher B.C. spire point instead of an inefficient round nose or flat nose costs you nothing while empowering you with more precise shot placement, even at close range. And should that occasion ever arise where you get a standing broadside shot of the only buck you’ve seen in three seasons — and it’s 250 yards away — you’re ready for it.

What About Even Higher B.C. Numbers?

For a better example of what a high B.C. can do for you, check out this next chart. This is a mythical cartridge throwing a 143-grain bullet with a B.C. of .625 at our same 2,850 fps.

6.5?, 143-gr. ELD-X, B.C. .625

How about those apples! Even though this bullet is 10 grains lighter than our 150-grain BTSP, it’s already retaining more energy at 100 yards. I suspect if you asked most hunters which would “hit harder,” a 150-grain .308 or a 140-grain .264, most would vote for the .308. Notice how the lighter bullet’s energy advantage increases with distance. This is conservation of energy at work.

As for trajectory curves, the 5-inch difference in bullet drop at 500 yards is becoming problematic. The 9-inch additional wind deflection certainly is. Differences like these are why the long rangers insist on high B.C. projectiles. A 9-inch reduction in wind deflection compensates for a lot of misjudging.

Mythical Cartridge to Make a Point

You might be wondering why I used a mythical cartridge and bullet in this last chart. It’s to make a point: cartridges and bullets matter only in what muzzle velocity they can churn up and what the B.C. rating is. Our mythical cartridge could be a 6.5x55, 260 Rem., 6.5-284 Norma, 6.5 PRC… Increase the caliber and weight of that bullet and it could be a .277, .284, .308 or .338. But if you keep B.C. and MV constant, trajectories will remain identical. Caliber and weight don’t change that because both are already factored into B.C.

The cartridge and caliber don’t change drop and deflection if the bullets they’re pushing match B.C. and MV.

Additional bullet weight does do something important, however. It increases kinetic energy at all ranges. So long as the B.C. and MV of any two bullets are the same, the heavier one will carry more energy. When you think about it, this ballistic reality is significant if you’re trying to maintain a certain impact energy level without enduring excess recoil. But it’s also possible that a lighter bullet with significantly higher B.C. can end up carrying more energy, more “punch” if you will, than a much heavier bullet with low B.C. This is how the puny little 6.5 Creedmoor can put more energy on target at 1,000 yards than some 300 Win. Mags.

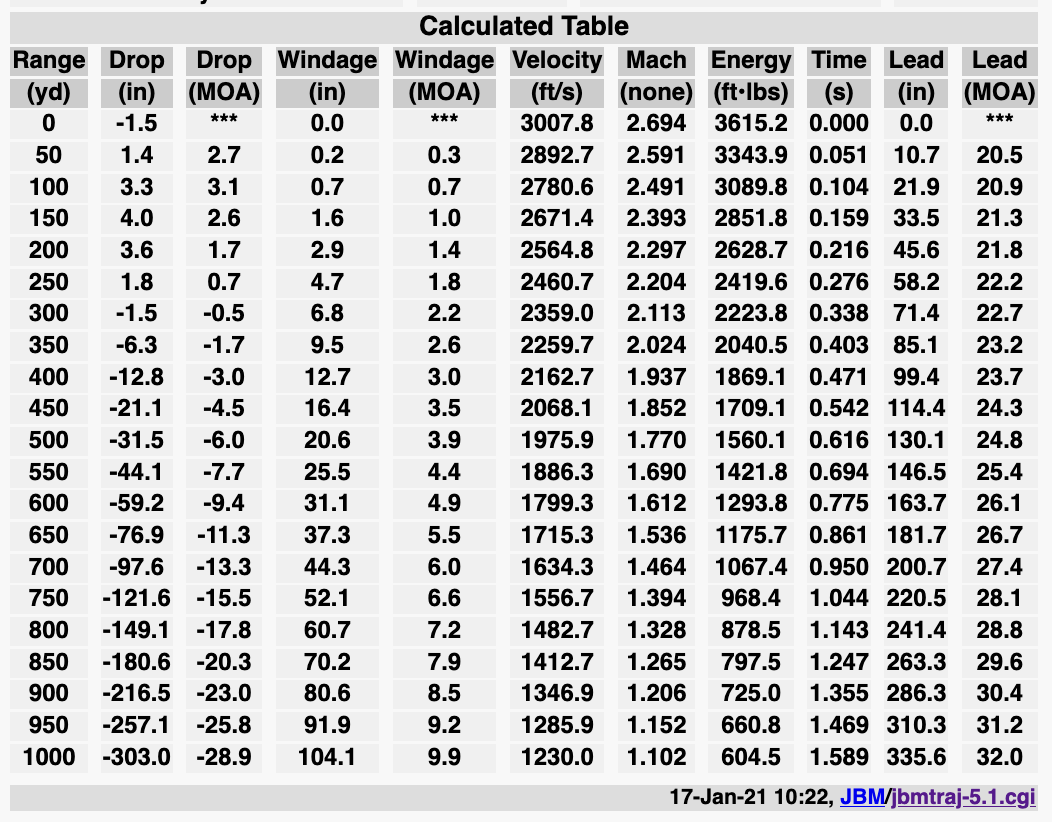

That’s correct. The puny 6.5 Creedmoor actually can put more energy on target at long range than can some popular 300 Win. Mag. cartridges. Before you laugh and leave, check out the following trajectory tables. They don’t lie. This is basic Newtonian physics. It might seem counterintuitive, but it’s real. Let’s run a ballistic chart on a 143-grain .264 bullet, B.C. .625 at 2,750 fps against a 180-grain .308 Spire Point, B.C. .425 at 3,000 fps. Instinctively we would imagine the heavier would “hit harder?” but…

Which of these two would you credit with delivering more energy on target? Trick question.

6.5 Creedmoor, 143-gr. ELD-X, B.C. .625

300 Win. Mag., 180-gr. SP, B.C. .425

Now if these two ballistic tables aren’t an eye opener you need another cup of coffee. Maybe a whole pot. Lordy lordy that 300 Win. Mag. starts life carrying 3,615 f-p energy to the dinky Creedmoor’s 2,409. A massive 1,206 f-p differential. That’s enough kinetic energy to lift 1,206 pounds a foot off the ground. Yet by 300 yards the 300’s advantage has been cut down by more than half to just 503 f-p. And at 800 yards our pipsqueak 6.5 Creedmoor bullet is actually packing 46 f-p MORE energy than the mighty 300 Win. Mag! At 1,000 yards it’s got 105 f-p more.

This doesn’t mean I’m advocating shooting game at 1,000 yards! I merely pointing out how B.C. ratings really do make a difference. A huge difference. But only at longer ranges! That’s the take away here. And only you can judge that for yourself and your hunting style, habitat, location, and shot distances. They may suggest you could get by with a lighter recoiling rifle.

Bullet shape can sometimes do more than weight to change impact energy. Choose carefully.

By the way, proponents of big bore sizes, bullet mass, and momentum are going to argue that a 180-grain slug at 1,230 f-p is going to penetrate and hurt more than a 143-grain at 1,495 f-p. Would you rather drop a bowling ball on your toe from six inches up or a ping pong ball from six feet up? On the other hand, big bullet advocates are always bragging them up for their “knockdown power,” their higher impact energies. Well, if kinetic energy constitutes knockdown power, the 6.5 Creedmoor wins at 800 yards, much as Creedmoor haters don’t want to hear that. Easy guys. It’s just physics.

Here’s another way to look at this: most of us know Newtonian law of conservation of energy. For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. In a hunting rifle this means the energy propelling the bullet forward propels with equal force on the rifle and shooter behind it. But would you rather be hit with the 8-pound rifle or the 140-grain bullet?

Here I am absorbing 67 foot-pounds of recoil from a Dakota M76 416 Rem. Mag. coughing up a 400-grain bullet at 2,500 fps. Trust me, I fared better at the butt than I would have at the muzzle. For perspective, a 30-06 shooting 180-grains at 2,800 fps kicks with about 21 foot-pounds.

Where am I going with this? I’m not sure anymore. I’ve dived so far into the weeds that I can’t see the thicket for the stems. But I do know this: bullet B.C matters. It matters a lot, especially for wind deflection and retained energy. But…

When B.C. Can Be Ignored

Bullet B.C. isn’t worth even considering if you engage all your deer, elk, coyotes or anything else at 100-yards or less. Or maybe even 200 yards. It does begin to matter beyond 200 yards, and can easily be the difference between a hit and a wound or miss beyond that. It costs little or no more to shoot a high B.C. bullet than a really low one, so, given reasonable hunting accuracy, the wise hunter opts for the higher B.C. bullet.

On the other hand, there are many hunters who believe round nose or flat nose bullets hit harder and kill faster than spire points inside of 200 yards or so. I’ve yet to see a description of how this happens, but that hardly matters to the folks who believe it does. Don’t underestimate faith when targeting dinner. A hunter who has absolute faith in his slow, heavy, stodgy old bullet with the basement level B.C. will likely make a perfect shot and clean kill every time.

Bottom line: don’t pretend that bullet B.C. means nothing. It clearly does. It means a lot. Just not for deer hunting inside 200 yards. Shoot what you like. Enjoy your hunting. Oh, and by the way, were I choosing a rifle/bullet for elk hunting, it would be the 300 Win. Mag., not the 6.5 Creedmoor.