Bullets Work This Way

Terminal bullet performance varies depending on how the bullet is made, at what velocity it lands and where on the animal it strikes.

In our last blog post (you can read it here) we deferred to Sir Isaac Newton and learned why the widely advertised “knockdown power” of high-powered, modern center-fire rifle ammunition is not really knockdown power at all.

So, if we can’t count on knockdown power to bring home the bacon, what?

Well, not velocity. Contrary to common belief, speed does not kill. At this moment you are moving to the east at about 1,000 miles per hour (the Earth rotates on its axis at that speed.) It doesn’t hurt, does it? But if you merely stroll nose first into a wall, ouch. That little bit of speed hurts because we’ve added something -- mass. Your’s and the wall’s. Mass alone can kill (try gently resting a truck on your chest.) But with rifle bullets you need both velocity and mass to damage vital tissue. And that’s the key to terminating big game: tissue damage. Not “knockdown power.”

You could “shoot” your venison every fall by gently lowering a massive object atop it, but deer rarely stand still for that. Dropping a 100-pound lead ball on them from 10-feet overhead isn’t likely, either. This is why we lighten our projectiles and add velocity. A 150-grain bullet weighs just 1/3 of an ounce, yet with enough velocity it can terminate a 2,000-pound eland. It can reach it from 300 yards, too. Let’s hear it for velocity!

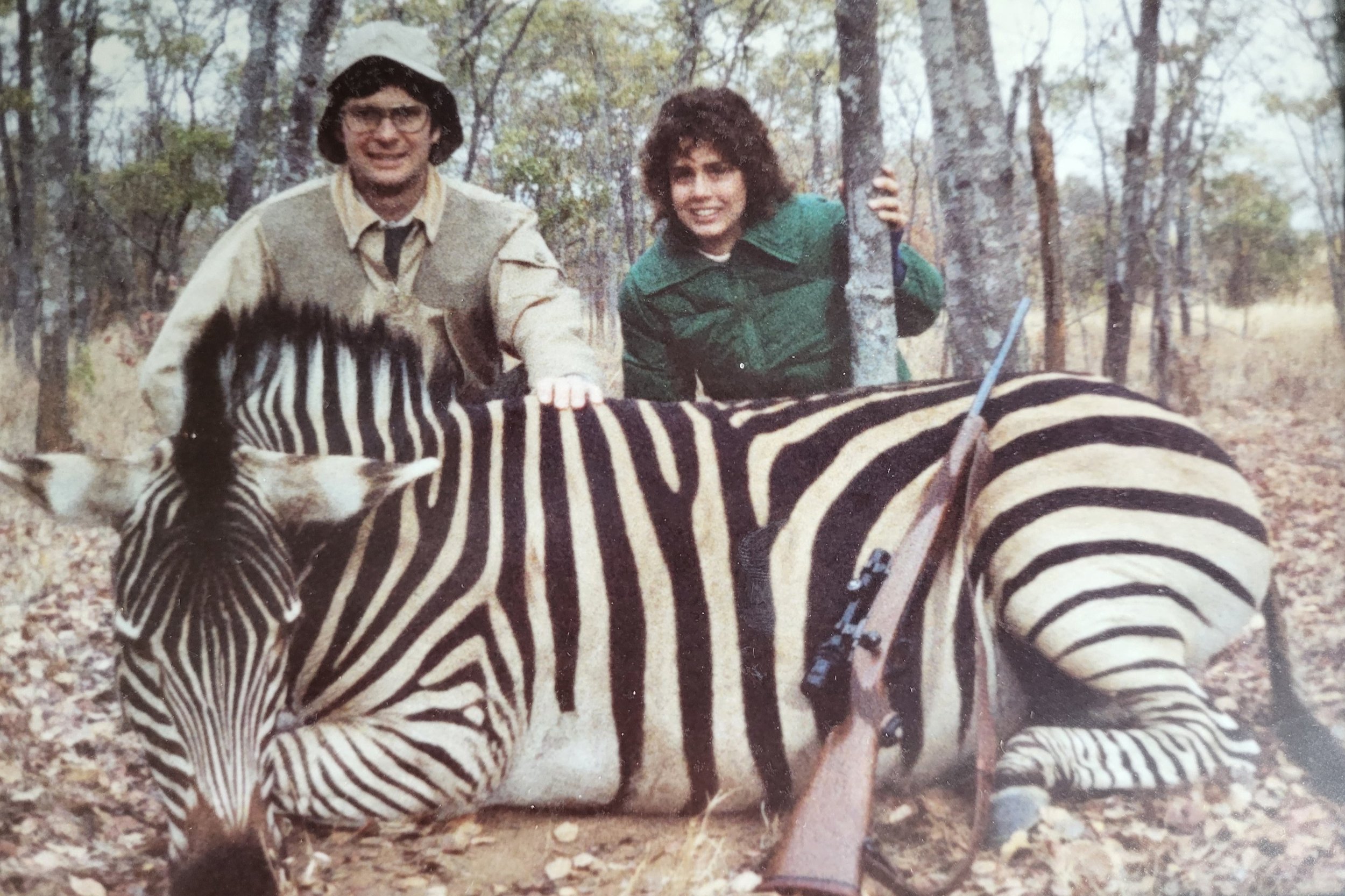

The worlds largest antelope, eland, weigh as many as 2,000 pounds, yet can be dropped with a single bullet weighing less than 1/3 ounce.

According to basic physics, if you double mass, you double energy. A 50-pound anvil resting on your foot should hurt twice as much as a resting 25-pound anvil. But double the speed and you quadruple the energy. The 25-pound anvil dropped from knee-height is going to hurt a lot more than the resting 50-pounder.

This is what shooters are looking for when they shop for “knockdown power.” A combination of speed and energy. That’s what kills. But how? With shock and awe?

Well, sometimes with shock (poorly understood and difficult to explain) but usually via the destruction of the animal’s central nervous system. Strike your deer in the brain or spinal cord, anywhere from the brain stem back to about the top of the shoulders, and it usually collapses on the spot, essentially dead instantly.

Solid heart/lung shots don’t usually get these same results. That’s because those are vital organs, but only because they supply brain cells with oxygen. So long as a deer’s blood pressure remains normal and fresh blood keeps delivering oxygen to the brain, it lives. Discombobulate the cardio-pulmonary system and the brain continues to function until blood pressure drops excessively. This could happen in a second or several minutes depending on how rapid the hemorrhaging.

Heart shot twice with 130-grain Winchester Ballistic Silvertip from a Mossberg 4x4 270 WSM, this whitetail continued courting a doe for many seconds before falling.

That’s why heart-shot deer, elk, etc. often run for several seconds before falling. It’s why broadheads (arrows) kill with virtually no kinetic energy. Hemorrhaging leads to a severe drop in blood pressure, and that causes animals to faint or pass out. This is what we commonly see when game shot “right in the boiler room” runs off as if untouched. It also explains why they soon veer off course, wobble and fall over. Lowered blood pressure. The animal feints into unconsciousness. Technically, I suppose, it wouldn’t be clinically “dead” for 10 minutes, since that’s when brain cells reportedly die.

This suggests the animal is suffering, but I doubt it. As humans under anesthesia prove, unconscious animals feel no pain. I’ve watched numerous beasts absorb major hits from both arrows and bullets with virtually no reaction. They’ve continued standing, walking, feeding, even mating. But when blood pressure drops too low, when insufficient flow of oxygen-rich blood starves the brain, they collapse and expire.

Norma's excellent, bonded, controlled expansion Oryx bullet can be counted on to retain most of its mass regardless what it hits and at what velocity.

Hitting the vital organs “harder” doesn’t necessarily damage them any more than slicing them lightly with a broadhead. We don’t need projectiles that hit harder so much as ones that cause maximum vital organ destruction. This is why mushrooming — bullet expansion — is important. A bullet that expands and exposes sharp, ragged edges creates more hemorrhaging than solid bullets that punch through like a target arrow. And this suggests a reason why bullet mass can be an important part of effective terminal performance. We’ll examine that in a future blog.

## #